Sustainability and climate change are on everyone’s agenda. We all need to play our part in solving the problem. But aviation has a particular challenge since it is such a visible source of pollution and subject to high levels of criticism, all of which puts at risk its access to finance. Assuming that Paris Agreement targets are strictly adhered to and that nothing is done, there will be 90% fewer flights in 2050 than today. This would have a huge impact on the industry itself and, crucially, on the economies and personal freedoms that the industry enables. Aviation must therefore put its house in order. This blog presents a framework for building sustainability into every aviation project decision.

For the last seven years, I have been working with air navigation service providers (ANSPs) across Europe, leading business cases, investment appraisals, and improving their processes around investment decision making. Together with colleagues, I have supported several banks with a review of their lending policy, specifically with the intention of accounting for sustainability. I have also helped the EIB with their work focused on providing lending facilities to the air traffic management (ATM) industry. This experience has shown me that planning and accounting for sustainability is not straightforward. It is made difficult by often competing needs and objectives, even across sustainability projects!

Our industry is full of interdependencies, regulations and complexities. It needs (we need) ways to simplify things to enable us to move forwards. It is what led me to develop a decision-making framework that I first introduced to audiences at World ATM Congress earlier this year in Madrid and will introduce to you here. I will start by taking a brief look at the problem the Framework is helping to solve. I will proceed to describe the three steps involved in setting up the Framework, and finish by considering the decision-making for a sample project, using the Framework.

The fundamental challenge: any change in aviation needs to optimise network performance, but the decision making is done by individual stakeholders.

There is no escaping the need to address sustainability. Our citizens, industry regulators, governments, and funding and financing providers demand it. We within the industry also demand it. But doing it will take finance, and the industry has been hit hard by the COVID-19 pandemic.

My take on all this is that planning for sustainability must become an inherent part of an aviation project investment decision and not just an afterthought - it needs building in at the start. Just like “conventional” investment appraisal, you need to consider both internal aspects (ie the direct impact on your own costs and benefits) and also the impact on other stakeholders: a project conducted by an ANSP must be put together in as sustainable way as possible, but it must also enable other stakeholders (ie airlines) to conduct their operations in the best possible, most sustainable way. Finally, projects must also be built to be resilient to climate change – because, in future, our industry will have to cope with higher risk of adverse weather, sea level rises and the like.

A 3-step framework.

On the face of it, the Framework is simple. It is intended to be applied at the highest strategic level and can then trickle down. It begins with defining some principles for your organisation that you intend to apply to investments. These are referred to as your internal sustainable investment principles.

It moves on to consider the ‘must haves’ which must be present for the assessment of the viability of the project to proceed - these are the prerequisites. Then on the flip side, it defines project attributes which would represent ‘red lines’ that you cannot cross. These deal breakers will stop the project from progressing. Having done this, you can create your decision framework.

Let’s work through these steps now, considering an example scenario to which a sustainable investment decision-making framework could be applied.

If you are managing an airspace that is reaching capacity, you might be asked to build in more local capacity, building in controller tools … but actually the problem might be better solved with something that provides strategic deconfliction, implying action by multiple stakeholders. You are asked to consider two possible projects: strategic deconfliction vs tactical deconfliction:

- Tactical conflict avoidance advisories by controller in a single air navigation service provider.

- Long term planning of trajectories with a view to avoiding conflicts by strategic modification of the trajectories.

We know it is hard to get a strategic tool implemented over multiple jurisdictions. It costs more in time and effort. The tendency has therefore been for the industry to take easier steps that build in tactical capacity rather than long term strategic capacity. The problem is that the tactical capacity tends to be more intrusive and lead to bigger changes to the trajectory, whereas strategic changes are more efficient.

How would you decide? You could apply this Decision-Making Framework to the question.

Step 1: Define your sustainable investment principles.

You will need to identify which of these principles, some or all, you intend to adopt. And then you will need to define statements to express each of the principles. For example: We only invest in projects which cut CO2.

Of course, in the real world some principles will be more important than others to different aviation players – depending on their strategic and operational contexts. So, a low-lying airport may be more concerned with showing that projects help with climate change resilience and evidencing pollution reduction measures, whereas a UAM vertiport may need to target sustainable innovation, operational efficiency and the circular economy.

Sample sustainable investment principles are presented in the diagram below.

Step 2: Define prerequisites and deal breakers.

Before deciding if a project is ‘go’ or a ‘no-go’, we need to make sure we have sufficient information to make an informed decision. I have come across situations where a decision whether to commence a project was made without sufficient consideration, resulting in challenges later on. As such, we must clearly define what information we must have access too, before proceeding with the assessment. These are our prerequisites.

So, if one of our principles is that the project must cut CO2, then we need to credibly understand what the impact of our potential projects on CO2 will be, before we commit to either of them.

When it comes to ‘deal breakers’ these will be the things which would stop the project from being approved. They could be budgetary, output-related, impact-related – or it may be that everything should be on the table, there are no deal breakers.

Returning to our example, a requirement to reduce CO2 would be our deal breaker. We would expect the tactical tool to redistribute traffic over a greater geographical area, resulting in increased trajectory lengths, fuel consumption and hence CO2 emission. The only solution would be fewer planes, leading to reduced capacity. As such, the tactical tool would not pass the deal-breaker review stage. With strategic deconfliction over a wider area with multiple stakeholders there is a very strong chance of achieving higher capacity with lower CO2.

Maintaining acceptable safety levels is likely to be another deal breaker and important to articulate from the outset. Eg. The project must result in a decrease of CO2 production and maintain acceptable safety levels. There is discretion at the start of a project to decide which are the deal breakers, but once agreed they are then set in stone.

Step 3: Create your decision framework.

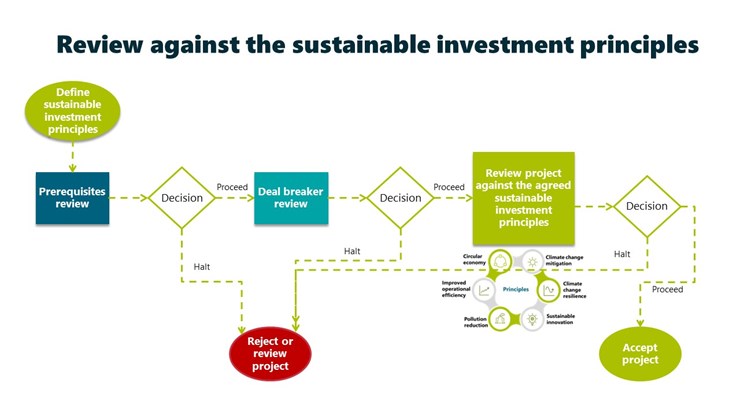

You have reached the point where you have set internal values, targets and objectives (your sustainable investment principles, taking account of the operating environment) and created a list of deal-breakers and prerequisites. This provides you with filtering criteria for your assessment framework, which you can test out internally and apply to decision making processes. The overview of the framework is presented in the diagram below.

Beneficial consequences.

We know how important it is to address public perception issues around aviation and appeal to funding providers. This framework promotes a sustainable culture within aviation by providing a systematic way of assessing climate impact. We need these tools to help us navigate our way through complex decisions. Even reaching agreement on prerequisites and deal breakers can be challenging. However, once those principles have been reasoned and agreed, the framework itself is easy to apply – effectively it becomes a new part of the usual investment appraisal.

We have also seen that it enables trade-offs to be made. The trajectory management example we explored here points to larger network level projects being favoured, despite the challenges they present. A surprising result is that previously rejected innovations become more likely to succeed. For example, an electric tow vehicle for incoming aircraft previously rejected for reasons of reducing operational efficiency (aircraft has landed and must wait to be connected to a tow vehicle) could now become more acceptable because of the beneficial impact on sustainability.

Do reach out to me if you would like to explore this framework further, and see how it could be applied to your internal decision making.